What, to the slave, was the Battle of Gettysburg?

Posted July 2nd, 2013 by James DeWolf Perry This essay is cross-posted from the Tracing Center on Histories and Legacies of Slavery, the organization which carries out the mission inspired by “Traces of the Trade.”

This essay is cross-posted from the Tracing Center on Histories and Legacies of Slavery, the organization which carries out the mission inspired by “Traces of the Trade.”

What, to the slave and to free blacks, was the Battle of Gettysburg? ((The title and first line of this essay are a paraphrasing of Frederick Douglass’ famous line, “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July?”, in his 1852 July 4th address, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” in Rochester, N.Y.))

Today marks the 150th anniversary of the start of the Battle of Gettysburg, which ran from July 1 to 3, 1863.

The Battle of Gettysburg is one of the most well-known events of the Civil War, and its sesquicentennial has been widely anticipated for years. Elsewhere, there are expert military historians to offer the most modern understanding of the battle’s tactical and strategic significance, as well as renowned civil war scholars to interpret the battle’s political and social significance in 1863, and to analyze the public’s memory of the battle in the last century and a half.

At the Tracing Center, we focus on the role of slavery and race in the causes, conduct, and consequences of the Civil War. The Battle of Gettysburg was certainly of strategic importance in determining the outcome of the war, namely, that the Confederacy would be re-incorporated back into the Union, and that emancipation would eventually become a reality throughout the nation. ((Even so, the Battle of Antietam was arguably more significant for the course of the war, and for its role in determining that emancipation would result at the end of the war.))

Beyond the battle’s military significance, though, what does the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg tell us about the role of slavery and race in the war, and about the battle’s importance at the time for free and enslaved blacks?

The role of African Americans in the Battle of Gettysburg

While there were many African-American troops fighting on the Union side by July 1863, relatively few of the nearly 200,000 black soldiers who would fight by war’s end were yet in federal service, and those black troops that were fighting were primarily assigned elsewhere during the summer of 1863. As a result, the evidence for any black soldiers at all fighting during the three days of the Battle of Gettysburg is uncertain at best.

The role of black troops in the broader Gettysburg campaign, however, is another matter. Black soldiers were involved in both fighting and in building defensive fortifications during the defense of Pennsylvania in June and July. One black company, in particular, was able to take up arms directly against forces under the command of General Jubal Early, who threatened Pennsylvania’s capital, Harrisburg:

Justice compels me to make mention of the excellent conduct of the company of Negroes from Columbia.

After working industriously in the rifle-pits all day, when the fight commenced they took their guns and stood up to their work bravely.

—Colonel Jacob Frick

Volunteer colored units are also known to have made themselves available for the defense of Pennsylvania, but were turned away rather than being allowed to fight.

Civilians were also impacted directly by the Gettysburg campaign. The town of Gettysburg itself, for instance, was home to hundreds of free black residents. Many of these residents, in far greater numbers than their white counterparts, had fled the area by the time of the battle. This was not out of concern for the expected clash of armies, however, but out of fear of “confiscation” by the Confederate forces.

In fact, black civilians had been fleeing their homes since mid-June, ahead of approaching Confederate forces, rather than face the risk of being “confiscated,” that is, being enslaved and taken into the Confederacy. This was, in fact, the fate of an unknown number of black residents of Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign.

Of note, however, the danger of being seized and taken into the South to be enslaved was not at all new to the black residents of Pennsylvania. The Fugitive Slave Act had made this an ever-present danger during the 1850s, and even prior to that time, roving gangs of slave-catchers would terrorize the Pennsylvania countryside, kidnapping those black residents suspected of being runaway slaves, and many who were not, and selling them into slavery in the South.

The sights and sounds of battle, however, were new to most black civilians in and around Gettysburg, and the experience caused many to rise to the occasion. Black residents of the area responded to the conflict by burying the dead and tending to the wounded and the dying, of both sides, to the extent that one journalist reported:

This is quite a commentary … upon Gen. Lee’s army of kidnappers and horse thieves who came here and fell wounded in their bold attempt to kidnap and carry off these free people of color.

Other black residents were inspired by the battle to enlist in the Union army, serving with distinction during the remainder of the war.

Not all African Americans at Gettysburg were northerners, of course. In the wake of the battle, 64 black laborers who had been traveling with rebel forces were captured by the Union. These are believed to have been among some 10,000 to 30,000 enslaved blacks performing contract work for the benefit of their white owners during the Gettysburg campaign. These 64 were taken to Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, famous as the birthplace of the National Anthem, and eventually, those who would pledge allegiance to the Union were freed.

The aftermath of Gettysburg for free blacks in the North

Beyond the immediate vicinity of Gettysburg, what was the significance of the battle for the black residents of the Union?

We’ve seen that there were relatively few black soldiers fighting on the Union side in the summer of 1863, and that black troops were actually turned away from the defense of Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign.

Yet this situation was slowly changing, as the Union gained experience with black troops and as military leaders and the general public continued to receive reports from Gettysburg and other military encounters. The heroic performance of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment at Fort Wagner, two weeks after Gettysburg, would accelerate the process, and all-black regiments would come to play an increasingly important role in the course of the war.

The Battle of Gettysburg had another direct and important consequence in the North: the New York City Draft Riots, which took place over July 13-16. The Draft Riots, while sparked by the drawing of names for the draft, were made possible because the Union troops ordinarily stationed in the city, along with the municipal militia, had been re-assigned to Pennsylvania for the Gettysburg campaign. The riot’s organizers were well aware of this fact, and took advantage to turn widespread frustration at the draft, and at the ability of the rich to avoid military service, into several days of burning, looting, and killing.

Despite the name, the Draft Riots were not aimed just at resisting the draft. The largely immigrant, working-class mobs were equally fearful about Lincoln’s stated intention to emancipate the Confederacy’s slaves after the war, and at what this might mean for their own jobs.

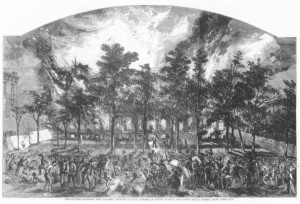

As a result, the mob’s violence was directed primarily at New York’s free black men, women, and children. Over four days, at least a dozen black residents of the city were lynched in the streets, while an unknown number were beaten and numerous black homes were burned. Notoriously, the mob also set fire to the Colored Half-Orphan Asylum on 5th Avenue, home to some 800 black children.

As a result, the mob’s violence was directed primarily at New York’s free black men, women, and children. Over four days, at least a dozen black residents of the city were lynched in the streets, while an unknown number were beaten and numerous black homes were burned. Notoriously, the mob also set fire to the Colored Half-Orphan Asylum on 5th Avenue, home to some 800 black children.

The mob in its brutalities regarded neither age, infirmity, nor sex. Whenever and wherever a colored population was found, death was their inexorable fate. Whole neighborhoods inhabited by them were burned out.

— Joseph Warren Keifer, Slavery and Four Years of War: A Political History of Slavery in the United States Together With A Narrative of the Campaigns and Battles of the Civil War in Which the Author Took Part: 1861-1865

In the end, the riots were only put down after the 7th New York Regiment was rushed back from the Gettysburg campaign.

The broader significance of Gettysburg for the nation’s black population

What broader lesson can we learn from the limited role of African Americans in the Battle of Gettysburg, and from the anti-black violence of the New York City Draft Riots?

These incidents, along with so much of the rest of Civil War history, show us that the Union was fighting this war not on behalf of those enslaved in the Confederacy, but for its own preservation, and that the North regarded free blacks, and the prospect of freeing millions of enslaved blacks in the South, with great hesitation.

In November, President Lincoln would travel to Gettysburg, for the dedication of the new Soldiers’ National Cemetery, and would famously give an address dedicated to the proposition that the Civil War was being fought not to end slavery, but to preserve the Union and the American form of democracy:

We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live … that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.

This is the president who had already taken the highly controversial position, in September 1862 and again in January 1863, that the Confederacy’s slaves ought to be emancipated at the end of the war. And yet he chose to focus his rhetoric here, as he almost always did, on the greater significance of the soldier’s sacrifice for his country, and not the moral cause of freedom for those enslaved by the Confederacy. He did so for the same reason that he faced a morale crisis among his own troops when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and would later have to struggle for passage of the 13th Amendment, ending slavery, at the end of the war: the Union public was badly divided over the question of emancipating southern slaves.

In a sense, then, the Battle of Gettysburg, and the broader military campaign of which it formed a part, were not the cause of the Union’s free blacks, nor of the Confederacy’s enslaved millions. Just as many black intellectuals had warned at the start of the war, this was not a conflict being fought over black freedom, and the struggle for emancipation was happening off the battlefield, not on it.

On the other hand, there was a profound transformation taking place, slowly, among the Union’s political and military leadership, and within its public, as a result of the role played by African Americans in and around battles such as these, in other heroic exploits such as Harriet Tubman’s Combahee River Raid, and in the other countless acts, large and small, by which African Americans fought for their own, collective emancipation. Through these experiences, much of the Union came to see the Confederacy’s exploitation of slave labor as unsustainable in a reunified United States, and to recognize the virtues of, or at least an appealing sense of moral redemption in, the liberation of that enslaved population after the war.

From this perspective, then, the Battle of Gettysburg may not have been the most important battle of the war as far as the nation’s black population was concerned, but it was far from insignificant.