The Emancipation Proclamation’s 150th anniversary in context

Posted January 2nd, 2013 by James DeWolf Perry This entry by James DeWolf Perry, who appears in Traces of the Trade and was the film’s principal historical consultant, is cross-posted from the blog of the Tracing Center, the nonprofit founded to carry on the mission inspired by our documentary, and originally appeared on January 1.

This entry by James DeWolf Perry, who appears in Traces of the Trade and was the film’s principal historical consultant, is cross-posted from the blog of the Tracing Center, the nonprofit founded to carry on the mission inspired by our documentary, and originally appeared on January 1.

Today is the first day of 2013. This is an anniversary year that we’ve been talking about, and anticipating, for a long time here at the Tracing Center.

In 2013, we will celebrate the 50th anniversaries of major civil rights era milestones, including the March on Washington and Dr. King’s legendary “I Have a Dream” speech.

Over the coming year, the nation will also mark the 150th anniversaries of the Battle of Gettysburg and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, as well as the New York City Draft Riots (the violence of which was aimed mostly at the city’s free black population) and a host of other Civil War battles and dates.

The anniversaries of the Civil War and the civil rights movement are directly connected, as they represent two different, but closely related, stages in our society’s slow process of reckoning with its centuries-long embrace of slavery and racism. Exploring these anniversary dates, their connections, and their broader significance for racial healing and justice will constitute much of the Tracing Center’s work in the years 2013-2015.

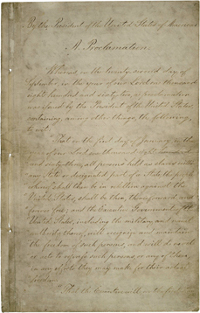

Today, however, marks the 150th anniversary of perhaps the greatest of all of these events: Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation marked a turning point in the history of enslavement in the United States, and generated momentum which, after much struggle, would lead to the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment and the abolition of slavery in this country. The Proclamation was also a political document: it was carefully designed to be limited in its effect, exempting those enslaved in Union states or in areas under Union military control, and aimed mostly at those held as property by the enemy. Even so, Lincoln was taking a calculated political risk in issuing the proclamation: his own advisers were opposed to the measure, many Union soldiers in the field were aghast to learn that they were now fighting for the freedom of southern slaves, and as the political maneuverings depicted in Steven Spielberg’s new film, Lincoln, would prove, a majority of the Union public was still firmly opposed to emancipation.

Thus this anniversary is not only an occasion for celebrating freedom, but also for somber reflection on how much the entire nation was supportive of slavery and how little would actually change as a result of the Civil War. The widespread public opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation, even in the northern and other “free” states of the Union, goes a long way towards explaining why emancipation was paired not with some rudimentary form of compensation, but instead with indifference, with other forms of forced labor, and with discriminatory Jim Crow laws and practices throughout the nation for another 100 years.

In fact, the Emancipation Proclamation illustrates, as well as any other single event, why it is that the 150th anniversary of the Civil War and the 50th anniversary of the civil rights moment are so intimately connected—why the civil rights movement is, in a broad sense, merely another chapter in a story that began with abolitionism and only reached a decisive middle with the coming of the Civil War.

Here is how King began his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in the summer of 1963:

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

King saw that the reluctance of the white citizens of this country, north and south, east and west, to emancipate 4 million slaves at the time of the Civil War led to a racial stalemate afterwards, in which freedom from bondage was not matched by liberty in any meaningful sense. He understood that the Union decided it had taken a moral stand in abolishing slavery, and thus washed its hands of any further responsibility for its role in two centuries of slavery. He realized that freeing slaves with no support whatsoever, and then imposing the most onerous restrictions on education, employment, and housing through generations of segregation and discrimination, had led to an enduring racial prejudice and inequality so crippling that it scarcely amounted to freedom in any meaningful sense.

In 2013, we must ask of ourselves as a nation, what progress have we made over the course of another 50 years since the civil rights era? In what ways have we made progress towards realizing King’s dream of an end to racial prejudice and inequality, and in what ways does his dream remain unfulfilled?

In other words, what remains today of the unfinished business of Civil War and civil rights?