A sad and sorry continuity: the North in Spielberg’s “Lincoln”

Posted November 17th, 2012 by katrina This entry by Producer/Director Katrina Browne is cross-posted from the blog of the Tracing Center, the nonprofit founded to carry on the mission inspired by Traces of the Trade.

This entry by Producer/Director Katrina Browne is cross-posted from the blog of the Tracing Center, the nonprofit founded to carry on the mission inspired by Traces of the Trade.

I’m one of the jaded ones now.

So it surprised me not to find Fernando Wood rearing his pro-slavery head again, this time as a Democratic Congressman from New York. Here he was on the big screen in Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, showing up in 1865 as a vocal opponent in Congress to the passage of the 13th amendment. I knew of him from four years earlier, when in 1861, as mayor of New York City, on the heels of South Carolina’s secession, he proposed that the city should also secede from the Union. He was well aware that New York’s economy was inextricably tied to slavery.

Once you know about the North’s complicity in slavery and racism you see the through-line almost everywhere you look. The winter-spring of 1865 that is the subject of Lincoln thus becomes just one more chapter.

In the popular, white, non-southern imagination, we put Lincoln on a pedestal, but we subconsciously put ourselves on that pedestal too, because he is our symbol of northern determination to end slavery. That was us. The good guys.

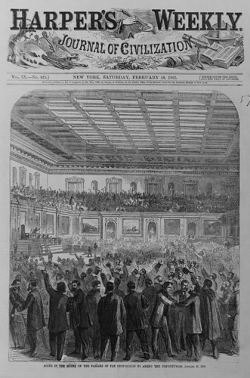

But Spielberg, along with screenwriter Tony Kushner and historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, whose book the film is largely drawn from, confront us with a drama that is not North vs. South. Congress, after all, had no representatives from southern states at that time; the latter had their own Confederate States of America. Rather, we see unfolding with great intensity, the efforts of President Lincoln to secure enough Republican and Democratic votes from Union states to pass the 13th amendment, and it is far from clear that Northern white men care to end slavery as much as they care to end the war. We see that Thaddeus Stephens and the Radical Republicans are in the minority in their belief that blacks and whites are fundamentally equal—that all are created equal. Even the narrower concept that black Americans should be seen as “equal before the law” is well outside the mainstream and Lincoln knows it. So he heroically exerts all his political and moral will, skill and capital to generate passage, and succeeds only within a hair’s breadth.

I’m jaded now, because this is where my attention has been for more than a decade—northern anti-heroism. But in seeing this powerful film, I couldn’t help think of how disillusioning some of these revelations would be for many Americans, especially white, non-southern Americans. I found my mind pulling me back to some of the moments in the education of this white woman that were most shattering and indelible. Those moments remind me of how deeply I was raised in one storyline and what a big deal it was to be confronted with good reason to rethink it at its core.

Here is one indelible moment. The occasion was during a research fellowship for filmmakers and artists at the American Antiquarian Society in 2000. I was digging into archival documents during the early development stage of Traces of the Trade. I was still trying to wrap my head around the fact that there had been slavery and slave trading in the North.

It seemed a bit of a digression, but someone suggested I look at AAS’s collection of minstrel show sheet music. So here they were now in my white-gloved hands in a quiet reading room. I was aghast. The racist stereotypes—whether of the happy slave, the buffoon, the step-and-fetch-it—that were their stock and trade (pun intended), were not just produced and consumed as entertainment in the South, but were coming to a large degree out of cities like New York. I learned that writers, performers, publishers of minstrel shows were thriving in the North and relied on northern audiences as much as southern. And this was during the 1840s, 50s, 60s and beyond.

So in 2000 this was the latest shock to my innocent notions. Here’s how the revelation went: “Oh my god! Even after slavery and the slave trade were illegal in the North, there was pervasive racism!” It seems so obvious and predictable to me now. Black Americans would have reason to scoff at my naiveté, but I remember the disbelief, the heartbreak, the feeling that I’d been fooled again. Weren’t we the good guys? If we had seen reason to abolish slavery in northern states, wasn’t it because we believed in freedom and equality for black Americans?

Not so—at least not as far as the majority went.

So here we are in the spring of 1865 with the through-line. Northern lawmakers were not clamoring to bring a full-scale end to slavery. Even those who backed the amendment didn’t necessarily believe in equality of the races. President Lincoln should not have had to fight so hard for what we now see so easily was the right thing to do. Black abolitionists (who are sadly off-screen in this film) should not have had to fight so hard.